‘Mutiny: Works by Géricault’ Review: Equine Passions and Anxieties, The Wall Street Journal

- MJ Andersen

- Sep 10, 2018

- 4 min read

Théodore Géricault used the iconic animal to capture his tumultuous world on paper and canvas.

M.J. Andersen Sept. 8, 2018

No one will ever satisfactorily explain the human fascination with horses. Yet when it takes hold of a gifted artist—Théodore Géricault, in this case—it becomes something more than a simple component of human nature. In Gericault’s work, horses filter the passions and anxieties of an age.

They are shown on the battlefield, at the race course, hauling coal, assisting street sweepers, delivering mail, attacked by lions—even dead. Though Géricault had little more than a decade in which to work (like a proper Romantic hero, he died in his early 30s), he amassed a record of equine existence that serves history and horse lovers equally.

“Mutiny: Works by Géricault,” on display at the Harvard Art Museums, offers a chance to rediscover this influential figure of the Romantic period. The exhibit draws from the museums’ substantial collection of Géricault’s works, particularly his lithographs. Géricault was one of the first French artists to make extensive use of the medium, in part because of lithography’s capacity to generate multiple images. Distributing lithographs, he hoped, might encourage sales of his paintings. Together with several drawings and prints, the three oil paintings in the exhibit point to Géricault’s more dazzling achievements, including his masterpiece “The Raft of the Medusa,” which hangs in the Louvre.

Géricault was born in Rouen in 1791. He came of age during the Napoleonic wars, primed to glorify soldiers. “Portrait of Olivier Bro” (c. 1818) captures the young son of a cavalry officer who was knighted by Napoleon.

Painted in somber tones, the boy sits astride a snarling dog and appears ready for action.

Géricault had the heart of a dramatist, and was as schooled in the costs of war as in its splendors. The early lithograph “Return From Russia” (1818), one of the more powerful images in the exhibit, captures two officers retreating through the snow after Napoleon’s disastrous Russian campaign. One, badly injured, rides an exhausted horse that competes for our pity.

What lithographs gain in literal detail they sometimes sacrifice in emotional force. “The Coal Waggon” (1821) ably depicts draft horses pulling a loaded cart. Yet they appear frozen in the moment, as if asked to pause for a photograph. A similar image in watercolor is more compelling. In “Coal Wagon Hauled by Seven Horses” (1821-22), a powerful team convincingly negotiates a corner.

Early in his career, Géricault learned by copying such artists as Titian, Rubens and Caravaggio, whose works he could study in Paris. Later, in Italy, he fell under Michelangelo’s spell. The muscular results turn up in his animals as well as his people. Géricault moved restlessly between the urge to imitate his masters’ classical forms and an impulse to document what he saw.

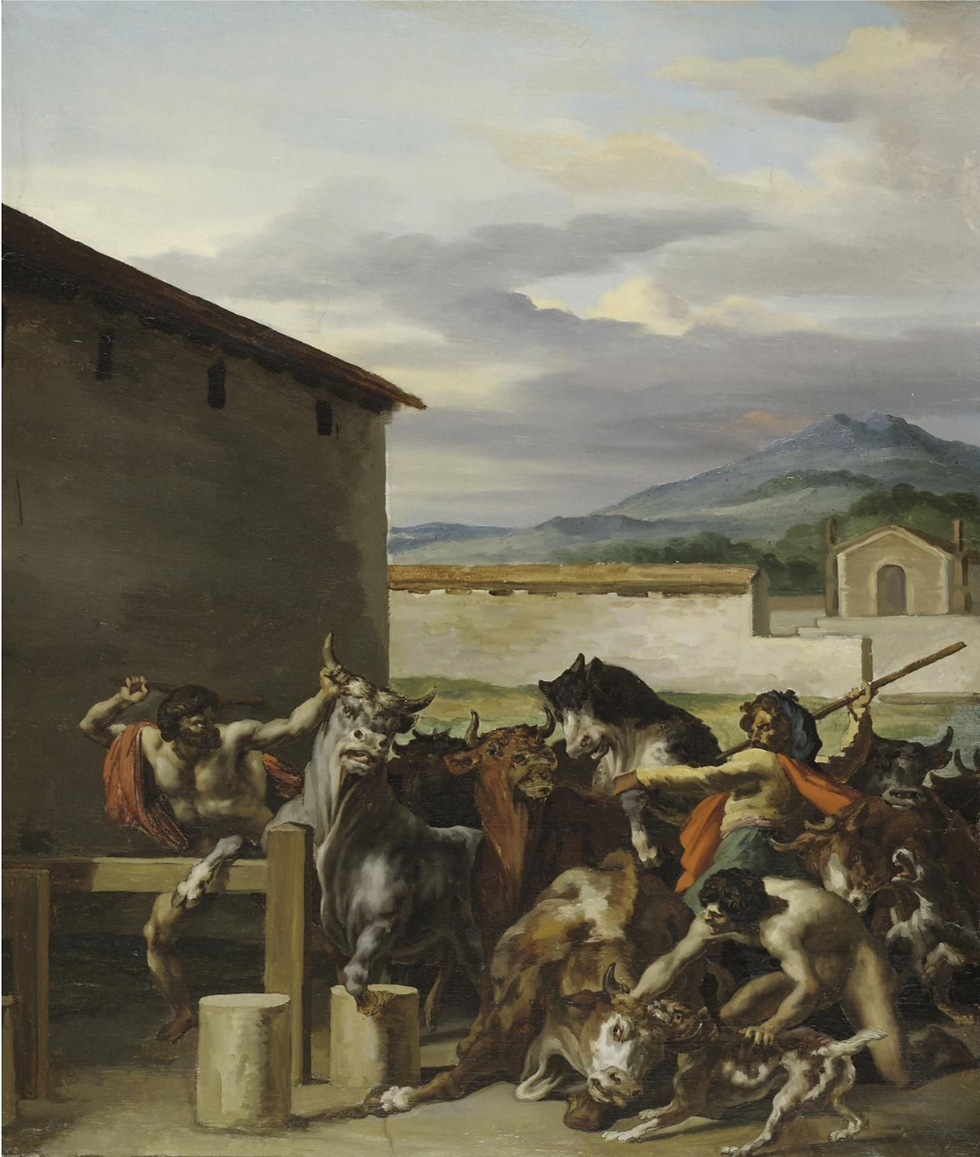

In the vividly painted “Cattle Market” (1818-19), a welter of hoofs, horns and

flared nostrils crowd the foreground. The animals’ faces are highly expressive: The two in the center almost appear to be chatting about their predicament. Behind them, a tranquil landscape radiates indifference.

Several works demonstrate Géricault’s facility as a draftsman. His sketches of a severed head are especially fine, and convey a quiet pathos. Along with other studies on view, they figured in the preparation for “The Raft of the Medusa.” Géricault based his painting on the scandalous case of a French ship that foundered off the coast of Africa in 1816. Only a few of the Medusa’s passengers survived after being cut adrift on a makeshift raft. Depicted on the verge of rescue, Géricault’s heroic survivors were seen as a rebuke to the ship’s captain and the restored government of the Bourbons.

In 1820, Géricault followed the completed painting to England, where it went on display. Struck by the vastness of London’s slums, he documented several scenes with lithographs. In one, a child holds a toy horse under her arm, as if the artist thought to provide his favorite comfort.

Not surprisingly, he was also attracted to England’s actual horses, and to the work of English artists, such as George Stubbs, who preceded Géricault in giving horses center stage. While he continued to depict the urban poor, Géricault also produced a series of horse lithographs, presenting the animals (for once) at ease, in a variety of settings.

His sympathy for the downtrodden extended to the emancipation movement. That feeling is represented here by “Man on a Rearing Horse” (c. 1825), a lithograph after a Géricault by Frederick Tayler. In it, a dark-skinned rider with exaggerated features manages to stay aboard as his mount charges into battle.

Taken together, Géricault’s creations reveal a man seemingly possessed by injustice. Yet if he was repelled by its cruelty, he was also fascinated. In the dispiriting aftermath of the French Revolution, horses, still so necessary to human enterprise, were the long-suffering objects of all that humanity had to dish out. Somehow, they were all the lovelier for it.

—Ms. Andersen is a former member of the Providence Journal’s editorial board and the author of “Portable Prairie: Confessions of an Unsettled Midwesterner” (Thomas Dunne/St. Martin’s).

Comments